It was winter 2014. Pharrell had just dropped Happy, the Rosetta probe landed on a comet, President Obama was opening diplomatic relations with Cuba…

…and here at Color, the bioinformatics team had a problem. Our pipeline — the data processing system that crunches raw DNA data from our lab into the variants we report to patients — was slow. 12 to 24 hours slow.

This wasn’t a problem in and of itself — bioinformatics pipelines routinely run for hours or even days — but it was a royal pain for development. We’d write new pipeline code, start it running, go home, and return the next morning to find it had crashed halfway through because we’d missed a semicolon. Argh. Or worse, since we hadn’t launched yet, our live pipeline would hit similar bugs in production R&D samples, which would delay them until we could debug, test, and deploy the fix. No good.

No quick fixes

We tried all the standard solutions. We wrote unit tests, which helped, but couldn’t easily cover the many parts that shell out to external tools or libraries in other languages. We tested parts manually, in both the command line and the Python REPL, but that quickly became tedious and didn’t catch regressions. We checked out an automated integration test that ran the whole pipeline, but it was much too expensive and slow to run on every commit, and running it nightly didn’t help our development cycle.

I was undeterred. I’ve seen the impact of short development cycles and feedback loops firsthand, and have spent much of my career identifying and ruthlessly cutting them — for data science here at Color, and elsewhere for web apps, Android apps, network ops, social network data and APIs, and small molecule visualization. Bioinformatics was new to me, but so what? I rolled up my sleeves and dove in.

s/dream/reality/

My goal was to come up with a tiny input dataset that the entire pipeline could run on, including all external packages and dependencies. I wanted it to run both locally and in our continuous integration environment. I wanted to generate a “golden” file with expected data that I could compare to the pipeline’s output data. And most importantly, I wanted it to run in seconds to minutes at most. I hoped that a small input DNA sample — just a few regions and 10k or so base pairs — would do the trick and still exercise most of the pipeline code paths.

I started with getting the full pipeline to run on my dev machine. Like many tech companies today, Color engineers use Linux in production but develop on Macs, so I had to find and build all the corresponding packages for Mac OS X with the same configurations and versions: R, Java, BWA, samtools, Picard, GATK, and many more. I also needed all of our datasets and related files in place, with the same directory structure as in prod.

brew install r

# if that didn’t install 3.1.3, and you don’t already have it installed, use

# this to install it: http://stackoverflow.com/a/9832084/186123

brew switch r 3.1.3

brew install homebrew/versions/gcc49 — with-fortran # takes 40m!

brew link r

brew pin r

Example: build and install R 3.1.3 with GCC 4.9 and Fortran support

I’ll spare you the details, but suffice it to say, matching our exact toolchain and environment took a lot of trial and error, and more than a little language inappropriate to a workplace environment.

Toy data in, toy data out

Once I got the full pipeline running on my laptop, I moved to the test dataset. I started with a well known test DNA sample from the NHS, and extracted one region in BRCA1 and one in BRCA2:

samtools view -b AH9TKMADXX_DS-152355_ACAAGCTA.bam 17:41255000–41260000 > chr17.bam

samtools view -b AH9TKMADXX_DS-152355_ACAAGCTA.bam 13:32895000–32905000 > chr13.bam

samtools cat -o pipeline_test.bam chr17.bam chr13.bam

# separate paired reads. https://github.com/samtools/samtools/issues/402

samtools view -uf64 pipeline_test.bam | samtools bam2fq → fwd.fastq

samtools view -uf128 pipeline_test.bam | samtools bam2fq → rev.fastq

# watch out for unpaired reads here, which BWA will die on with

# “paired reads have different names” errors.

# https://github.com/alexdobin/STAR/issues/45#issuecomment-108522238

java -jar /resources/picard/SamToFastq.jar INPUT=pipeline_test.bam FASTQ=fwd2.fastq SECOND_END_FASTQ=rev2.fastq

Extract two small test regions from a BAM file, then generate a FASTQ file

(Coordinates in FASTQ files always start from 0, so I also had to shuffle them down in the test FASTQ file to match.)

;; Open each VCF file, put point at first char of location (second column) on

;; first line of each chromosome, 13 and 17, and run this for each line as a

;; keyboard macro.

(defun shuffle-location ()

(let* ((bounds (bounds-of-thing-at-point ‘word))

(pos (apply ‘delete-and-extract-region (car bounds) (cdr bounds) nil)))

(save-excursion

(insert (int-to-string (- (string-to-int pos)

32895000 ; for chr 13

;41255000 ; for chr 17

))))

(let ((line-move-visual nil))

(next-line))))

Emacs Lisp for shuffling down DNA locations in VCFs

Finally, I made the golden VCF file with the test sample’s variants in just these two regions:

echo “chrom\tchromStart\tchromEnd\n17\t41255000\t41260000\n13\t32895000\t32905000” > positions.bed

for f in *.vcf; do

vcftools — bed positions.bed — recode — vcf $f

mv out.recode.vcf minimal/$f

done

bash snippet for extracting test regions from VCF files

Data, data everywhere, and way too much to drink

Now I could run the pipeline end to end on my laptop, and I had a tiny piece of input DNA to give it. Many of the pipeline stages used their own reference datasets, though, which could be gigabytes or more. And I hadn’t touched any of them yet.

Sure enough, I ran the pipeline locally on my test data and it took almost an hour. Definitely better than 12–24h for a full-sized input sample, but still way too long for a decent iteration loop.

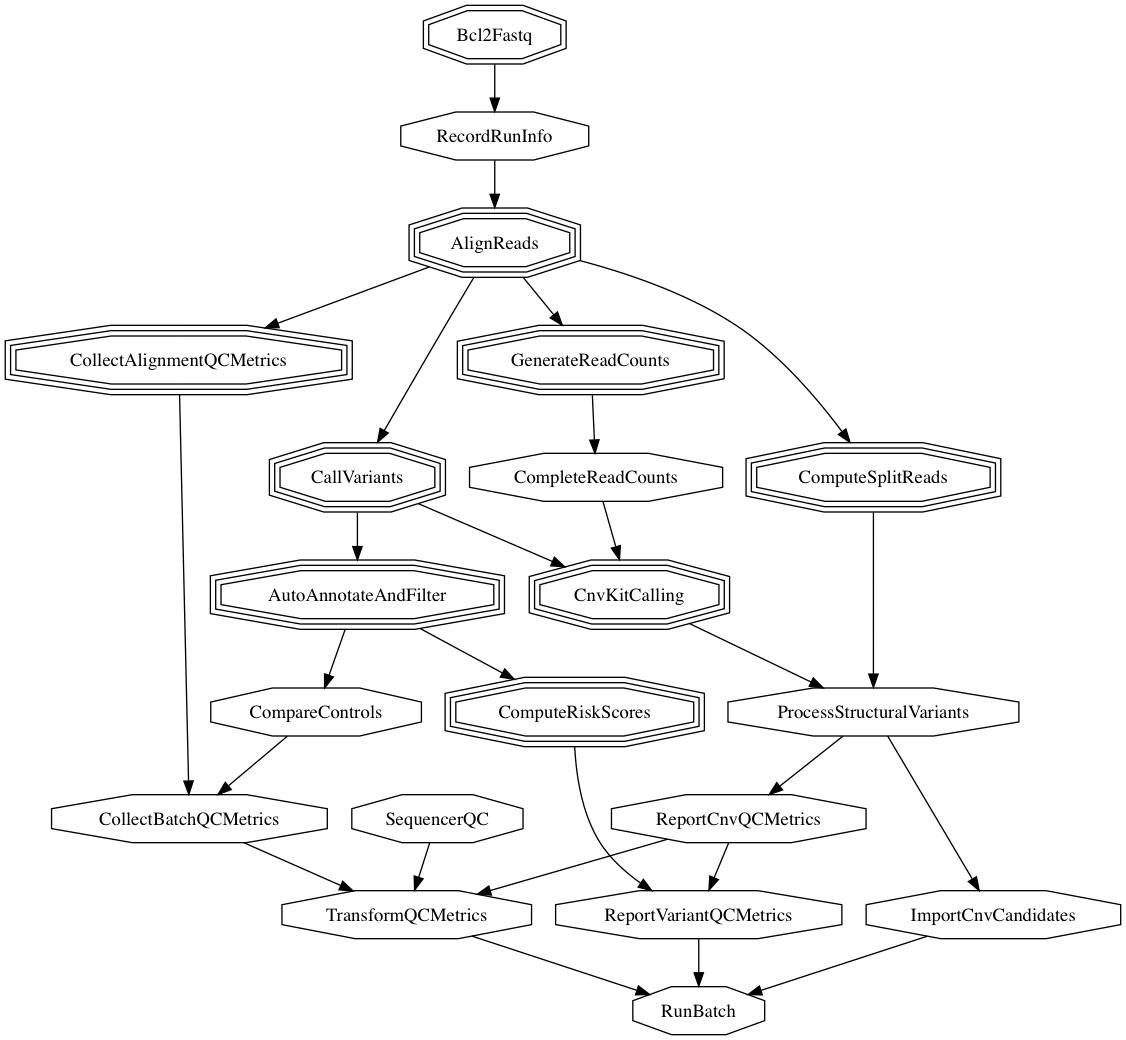

The task was daunting. The pipeline had dozens of stages, and each one did a different combination of tasks. Some used entirely homegrown code and internal data; others used multiple third party packages and datasets from across research, open source, and proprietary companies. They came in different languages and compiled binaries, and the data files ranged from CSV to XML to compressed and binary files with no identifying magic header bytes that file(1) threw up its hands on. The low hanging fruit was long gone. Our pipeline four years ago. It’s changed a lot since then!

Our pipeline four years ago. It’s changed a lot since then!

Our pipeline four years ago. It’s changed a lot since then!

Nonetheless, I dove into each stage, identified the packages, data files and other dependencies, and figured out how to cut them down and then reconstitute them so they were still usable.

Lots of different things used the reference genome, so I started there…

cd ../hg19/sequence

samtools faidx chr13.fa chr13:32895000–32905000 > chr13.fa.minimal

samtools faidx chr17.fa chr17:41255000–41260000 > chr17.fa.minimal

# remove location indices from headers in those output files ...

# remove offsets ...

…and moved on to the rest, one by one, debugging line ending compatibility issues:

# CaptureRegions.bed has CRLF line terminators. ugh.

tr ‘\n\r’ ‘\0\n’ < ../../r.full/PlatformInput/CaptureRegions.bed \

| grep -E ‘^(chr13.3289[5–9]|chr17.4125[5–9])’ | tr ‘\0\n’ ‘\n\r’ \

> CaptureRegions.bed

# shuffle locations down with Emacs Lisp snippet above

I decompressed, split, extracted, modified, and recompressed. Endlessly.

gunzip gencode.v18.annotation.gtf.gz

(grep ^”#” gencode.v18.annotation.gtf ; grep -v ^”#” gencode.v18.annotation.gtf | sort -k1,1 -k4,4n) | bgzip > sorted.gff.gz

tabix sorted.gff.gz

grep -E ^”#” gencode.v18.annotation.gtf > min.gtf

tabix sorted.gff.gz chr13:32895000–32905000 chr17:41255000–41260000 >> min.gtf

# shuffle down locations in min.gtf

bgzip -c min.gtf > src/datasets/etc/pipeline_test/gencode.v18.annotation.gtf.gz

git add src/datasets/etc/pipeline_test/gencode.v18.annotation.gtf.gz

I trial-and-errored, and trial-and-errored, and trial-and-errored:

grep -E ‘(chr13.3289[5–9]|chr17.4125[5–9])’ chainSelfLink.txt \

> ../../../../r/UCSC/hg19/annotation/chainSelfLink.txt

# expand a little since none were in our exact regions

grep -E ‘(chr13.[+-].328|chr17.[+-].412)’ refFlat.txt \

> ../../../../r/UCSC/hg19/annotation/refFlat.txt

# expand a little more...

grep -E ‘(chr13.[+-].32|chr17.[+-].41)’ refFlat.txt \

> ../../../../r/UCSC/hg19/annotation/refFlat.txt

# shuffle locations with emacs snippet above

I lsofed and straced, reverse engineered mystery file formats, decompiled and modified the incomprehensible resulting code, then recompiled. I examined each stage, each tool and file, learning its data and cutting down as small as possible. I ran the pipeline over and over and watched its running time drop from over an hour, to under an hour, to 30 minutes, 15 minutes, 10, 5, and finally just over 2 minutes.

“Dragon egg hatches!” JesseAndMike

“Dragon egg hatches!” JesseAndMike

Now, I must say, I was ecstatic. I wrapped it up in a test harness that used the test data, compared it against the golden output VCF, added a couple commands to our toolchain to install the dependencies, set up the environment, and ran the test. I helped our other bioinformatics engineers get it running on their laptops and added it to our continuous integration server. It started running on every single commit to our codebase. Victory.

Blood, sweat and tears

Our pipeline has grown substantially since I first put this together. We’ve switched out some dependencies, added some new ones, and expanded the pipeline to handle many more genes and genetic features. We’ve added many more unit tests and tools.

Even so, on every change to the pipeline we’ve continued to run this test both locally while developing and in our continuous integration environment. It has sped up our development cycle substantially, prevented countless bugs and regressions, and freed us to iterate and explore in real time, without fear.

This project was one of the most unusual, challenging, and rewarding things I’ve done in my career. If it sounds interesting to you too — frankly, if you’re even still reading this — let’s talk. We’re always looking for engineers who want to use technology to help improve our healthcare system. Reverse engineering strictly optional.

10,000 Year Clock, Long Now

10,000 Year Clock, Long Now

“Simon Says,” GamesMediaPro

“Simon Says,” GamesMediaPro

Reads