This is the first “homework” assignment for a Terra.do class I’m taking on the climate crisis:

The year is 2040. The world has figured out a pathway to radically reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, while also rapidly developing local communities’ capacity for resilience to climate impacts….You feel happy, and proud, because you played a role in making this happen. Please write a blog post…telling your story.

It’s been a rough couple decades. The COVID-19 pandemic shook the world to its core, grounding it like a misbehaving teenager. The few countries that managed to get on top of it early emerged into an oddly balkanized world, with neighbors and trading partners still locked down, and economies and supply chains in disarray.

The demand shock cost the world trillions of dollars and decades of growth. ESG budgets were slashed worldwide. Carbon pricing schemes were postponed, neutered, and in some cases, rolled back altogether. COP26 in Copenhagen was delayed, delayed again, reluctantly moved online, and passed with barely a whimper. Delegates who’d based whole careers on body language and facial micro-expressions suddenly found themselves lost in a sea of pixellated heads and muted voices. Not a single resolution was passed.

And yet. The world shook itself off, stumbled to its feet, and haltingly pulled itself back to work. Economies grew again, one by one, people felt safer, bit by bit, and they remembered what they’d seen. The Himalayas towering over India. Blue skies over Shenzhen. Streets full of people instead of cars. The night sky ablaze with stars. People remembered, and they demanded change.

Indonesia was the first. Monsoons had grown more and more extreme due to climate crisis, washing away entire villages with regularity. By late 2023, Indonesians had had enough. They voted in opposition leader Puan Maharani in a surprise upset victory, based on his platform of aggressive decarbonization and massive levy-building.

Latin America was next. Activists and indigenous elders had banded together to form the Iremos Vivir (We Will Live) movement in 2019 after the devastating Amazon wildfires, but it fell apart during COVID. As the region emerged from lockdown, the movement rose back up and swept across Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Ecuador, pushing a ratchet-based carbon tax and strict new emissions requirements for all trading partners. By the beginning of 2025, the Cinco Vivir – as the five countries called themselves – had revived the disgraced Union of South American Nations, convinced 14 of the 19 South and Central American countries to join, and ratified the majority of Iremos Vivir’s plan.

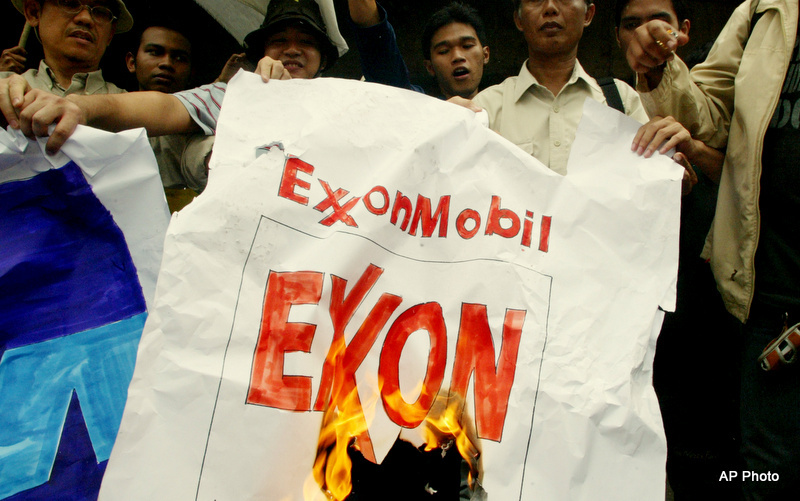

Multinationals saw the writing on the wall when ExxonMobil fell. For years, the protests at their annual shareholder meetings had grown, eventually rivaling Burning Man and Carnival in sheer size and exuberance. Independent estimates put the 2027 gathering at over 500,000, and the thunderous “Hey, hey, ho, ho! No more oil, it’s got to go!” was heard in suburbs over 10 miles away.

When it was over, chairman Everett Pritchard climbed into his bulletproof Range Rover scared, frustrated, and exhausted. Nine days later, he convened an emergency board meeting. A week after that, Exxon issued the now-famous #MicDropOilDrop press release:

We have known for decades that we need to turn and face the future. Oil extraction was already a net negative for shareholder value over the long term, and we now believe over the short term as well. Our employees have labored valiantly and made great strides, but not enough to outrun the innovator’s dilemma. We therefore plan to wind down our oil business units altogether and convert the company fully to clean energy and related industries by 2032.

The dam burst. By the end of the year, Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Pemex, ConocoPhillips, and 15 smaller petroleum production companies had made similar commitments. In 2028, Iremos Vivir strong-armed Petrobras and PDVSA into joining them. When Saudi Arabia and Qatar followed suit later that year, announcing that they’d replace their citizens’ coveted oil dividends with sovereign wealth fund payouts, a staggering 52 million barrels per day – 61% of global production – was slated to evaporate within five years.

Citizens and consumers worldwide demanded carbon prices from their governments and negative emissions commitments from their companies. Carbon markets had grown steadily over the last two decades, totalling 22Gt/yr of Co2e in January 2035, but measurement techniques had not kept pace. GHG Protocol had calcified, leaving most companies with error bars of 60-90% around their scope 3 emissions. Back in 2020, just 9% of the world’s revenue occurred in carbon priced jurisdictions, at a token cost of $6 per ton, so no one cared that – in one memorable CEO’s words – “the points are all made up and the rules don’t matter.” By 2035, however, the global share of carbon priced revenue had grown to 72%, and the average price was an eye-watering $59 per ton. The points and the rules suddenly mattered.

Baosteel / Glacier Media Group

Baosteel / Glacier Media Group

Consultants and operations people knew their supply chains inside and out, and they traded NDAs liberally and .xlsx models grudgingly, but the emissions numbers – the “points,” as it were – really were still all made up. To find the real numbers, they’d have to trace each SKU back an average of 9 vendors, 6 manufacturing and assembly facilities, and 17 transportation steps. Think all those iron smelters and cement curing shops kept particle readers and methanometers on every smokestack? Recorded them diligently and reported to every customer, amortized and broken down by exact contribution to each invoice line item? Fat chance.

Enter your humble correspondent. He pounded the pavement, cold called factory owners, sweet-talked floor managers, and typed in numbers until his fingers cramped and his eyes blurred. It took two years and seven months of soul-crushing grind, but at the end, he had a database of 63 million SKUs and their exact emissions, by molecule, down to the gram. When he finished with his first customer and saw a standard deviation of just 4%, he almost cried with relief.

By 2040, 241 of the Fortune 500 were using his database and software, along with 120,000 other companies worldwide. Its official name was Thermometer, but most people referred to it by its unofficial nickname: Carbon TurboTax. He could live with that.

Don McCullough

Don McCullough

Ryan Barrett

Ryan Barrett

Irwin Fedriansyiah / AP

Irwin Fedriansyiah / AP

Exxon’s recent activist investor uprising wasn’t far off from shareholder meeting protests and #MicDropOilDrop. Three board seats is a good start!