A while back, early in the blockchain hype cycle, a startup called Verisart popped up and promised to “fix” fine art. Not sure if that painting is real? Can’t find out who owns it, or where they got it? Worried that the gallery you’re emailing is a scammer? Worry no more! Verisart puts it all on a magically secure blockchain, and poof! No more problems.

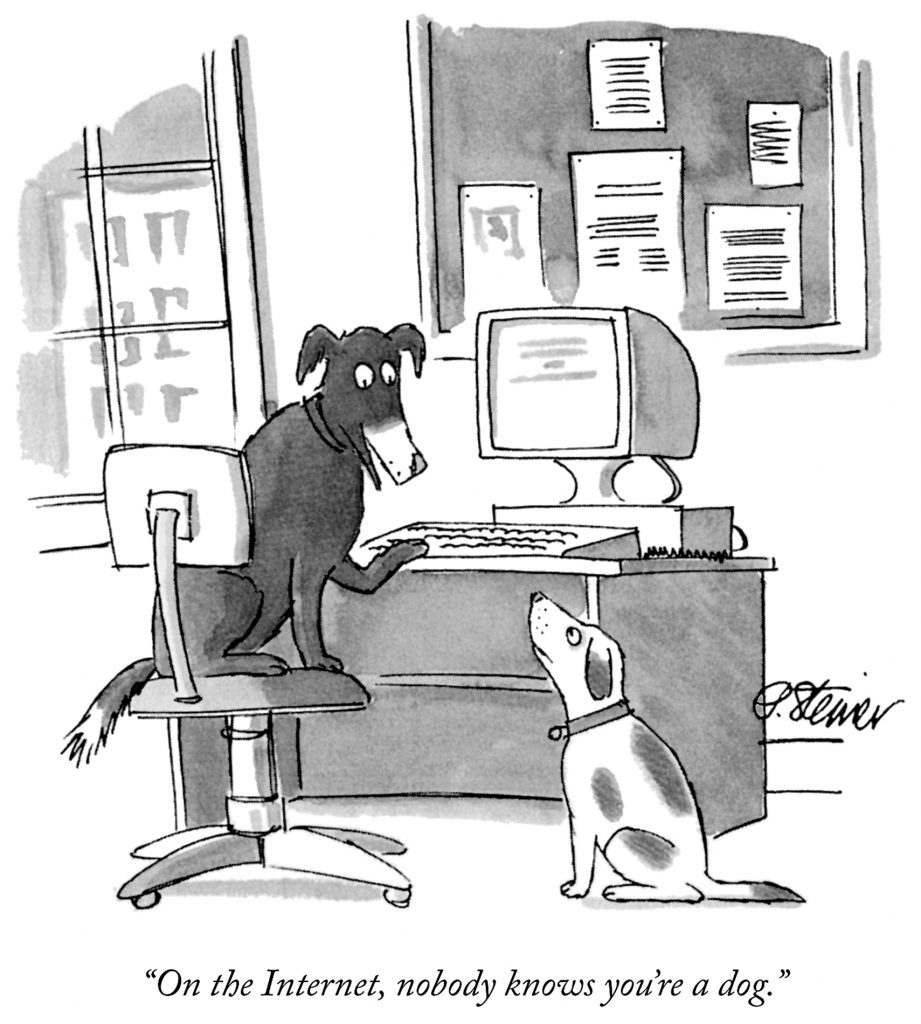

It wasn’t long before “digital troublemaker” Terence Eden created a Verisart account, told them he owned the Mona Lisa, and they dutifully accepted it and published it permanently on their “secure servers” and “most trusted” blockchain.

Long story short, I convinced them that I painted the Mona Lisa. An excellent situationalist prank. Much avant-garde, so postmodernism.

Funny joke, right? Blockchain fans cried foul, everyone else had a good laugh, we all moved on. The blockchain didn’t go away, though. More and more people are connecting it to the real world now, in more and more ways, and it’s not up to the challenge. Its strengths do not apply to the offline, off-chain world. The blockchain has a real world problem, and we’re not talking about it enough.

The blockchain has proven it can do two things well: cryptocurrencies and smart contracts. When it was introduced in 2008, Bitcoin successfully solved double spending and created a distributed immutable ledger, two core building blocks for digital currencies. Later blockchains like Ethereum added smart contracts based on decentralized consensus. These are striking, powerful new computer science primitives, and those don’t come around often.

Encouraged by that early success, people quickly tried to expand blockchains to other purposes. Startups popped up to provide currency exchanges, organizations, NFTs, real estate, carbon offsets, supply chains, even full fledged nation states. Notably, these often touched the physical world. Cryptocurrencies and smart contracts may exist entirely inside computers, but land doesn’t. Neither do paintings, greenhouse gases, or assembly lines.

Nevertheless, people breathlessly started building cryptocurrency tokens and blockchain services to track and “prove” real world claims. These are formally known as blockchain oracles. Blockchains are closed systems, with no built in way to interact with outside data. A blockchain oracle is a system that fetches off chain data and publishes it on chain. Early oracles stayed close to home, publishing cryptocurrency exchange rates and data from other chains, but later systems quickly spread further afield. Chainlink, one of the best known providers, publishes all sorts of real world data onto the Ethereum blockchain.

Armed with this technique, the art world looked like a ripe target. 91% of the art auction market is currently controlled by the Sotheby’s and Christie’s duopoly. Could a new, decentralized, blockchain-based fine art platform loosen their grip on the industry? The tech world certainly thought so. Maecenas, Codex, Verisart, Blockchain Art Collective, and others all jumped into the fray, swinging blockchains at canvases like broomsticks at a piñata.

They didn’t find candy inside, though. Selling and valuing fine art depends on verifying three things: authenticity (Is this the real Mona Lisa?), ownership (Who owns it right now?), and provenance (Who owned it before? How did they get it?). These are all real world questions, outside the blockchain. If Maecenas or Codex asserts that Alice owns the Mona Lisa, how do they guarantee that it’s actually true?

Mostly, they don’t. It took Verisart three more years to start verifying identities and authenticating works, and only for original artists already participating in their program. They never figured out authenticity or provenance otherwise. Instead, they pivoted heavily to NFTs, which are less problematic. Likewise, Blockchain Art Collective seems to be defunct, Maecenas too, and Codex retreated from the problem entirely, its founder demurring “Codex itself isn’t designed to provide provenance information.”

Artory may be one of the few exceptions. Like the rest, they’re now heavily focused on NFTs, and they seem stalled at Series A, but they do partner with real art appraisers like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Winston to verify authenticity and provenance. This is good! If any startup wants to be a believable source of record for fine art, that’s exactly what they need to do.

However, this significantly changes how they work. Verisart, for example, was originally an open, decentralized platform. Anyone could jump on and claim they owned a painting, and that they’d bought or sold it to anyone else. Artory, on the other hand, doesn’t allow that. Users can submit claims, but Artory has the sole authority to approve and publish those claims.

At this point, Artory is no longer decentralized in any meaningful way, which makes its blockchain less important as a building block. What do they get out of it? If they switched to a bog standard database, would they lose anything? Well, maybe. Anyone can download the Artory blockchain and see its entire history. If they used a database instead, they could let people download the data, but they’d have to take Artory’s word that it was complete and accurate, and that Artory wouldn’t change it later.

Blockchains have built in safeguards that guarantee integrity, ie these are the real contents, and immutability, ie users can only append new data, not change existing data. This is a less common feature for databases, but it is possible. Vitra is one example. The Internet Archive is another: it provides a comprehensive, independent historical record of a large swathe of the internet.

Blockchain provenance projects like Codex have tried to address this single point of failure. Codex works with multiple appraisers, auditors, and verifiers. Users may be able to choose the ones they want to work with, but Codex still vets them all first. This adds a layer of indirection, which computer scientists love, but doesn’t change the core problem. Verisart users must trust that it reliably verifies its artists’ identities; Codex users must trust that it reliably vets its verifiers. Either way, users have to trust a single human organization.

Other blockchain oracles combine data sources in more creative ways. Chainlink, the leading blockchain oracle provider, provides some equity prices and currency exchange rates on chain by fetching quotes from multiple sources and averaging them together. They do the same with weather, sports, news, and much more.

Regardless, these are variations on the same theme. Cryptocurrencies and smart contracts truly do reduce the need for trust and centralization! However, if you want to connect them with off chain data, you need to trust the source(s) of that data. Some oracle providers like Artory vet their data sources stringently, but many, like Chainlink, don’t:

Data providers can get a Chainlink Node quickly spun up and ready to sell data to smart contracts in less than 10 minutes. Chainlink is an open-sourced technology just like Linux and Python, so you don’t need our or anyone’s permission to set anything up, you can just go.

Caldarelli et al echo this in Understanding the Blockchain Oracle Problem: A Call for Action:

While the [blockchain] platform could be decentralized and independent from a central authority…oracles are unlikely to also be decentralized and autonomous. The chance for those centralized sensors to be free and independent from a central authority…is indeed quite low. An external authority monitoring those procedures is essential for the system to work correctly.

Blockchain fans may still believe it’s destined to replace current exchange systems like NASDAQ and SWIFT as a superior, decentralized alternative. Maybe someday! But not today. Witness Bitcoin’s 10 minute block time (transaction delay), Ethereum’s $10-150 gas price (transaction fee), both chains’ dozens of transactions per second vs Mastercard’s and Visa’s tens of thousands, and the whole ecosystem’s striking recentralization at scale. It may be improving on many of these metrics, sure, but the incumbents are too.

At this point, the blockchain starts to look less like a disruptive, transformative piece of technology and more like just a bad database, a database that hates you.

So where does this leave us? Cryptocurrencies and smart contracts are still fascinating. True, they’re often also dumpster fires, but the blockchains underneath them will improve over time. Technology always does.

However, next time you hear someone say they’ve taken a real world problem and solved it by putting it on the blockchain, ask them how. How do they authenticate the data? How do they vet the systems that do that authentication? How does the data get onto the blockchain? The more guarantees they make, the more they’ll depend on off-chain tools, procedures, organizations, and people. Always people. Verisart punted on many of these problems, as did most of its cousins, but that didn’t make them go away.

Blockchain and smart contracts are truly groundbreaking advances. They fascinate me. I hope they mature and succeed. However, we had to trust people before blockchain, in all sorts of ways, and we still do now. It’s the basis of modern civilization. This is a good thing, not a bad thing. Let’s remember that.

Perhaps blockchains will have bigger impact on building new digital native systems (which sufficiently interoperate with existing systems) than replacing/decentralizing existing “real world” systems.

Oracle space is changing. See Ergo’s Oracle Pools.

https://ergoplatform.org/en/blog/2021-04-27-chainlink-oracles-vs-ergo-oracle-pools/

Interesting! Originally I guessed web of trust style, but after reading, it sounds like financially incentivized reputation scores? I’m not sure that will provide the strict guarantees these use cases often need, or meaningfully add back decentralization in practice, but I’ll definitely stay tuned!

The art world using using blockchain this way makes me think “what if banking worked like DNS?” and then I pee myself a little.