Stop me if you’ve heard this one. When the last presidential campaign rolled around, Barack Obama wasn’t excited about business as usual. Instead, his campaign hired a bunch of smart techies, whipped databases into shape and mined them until they cried uncle, raised more money and mobilized more volunteers than ever before, and coasted to victory while reporters fawned over his Internet savvy and hard-nosed number crunching.

Oh, you’ve heard it? How about this one: Obama was originally against gay marriage, but he famously changed his mind a couple years ago when public support gained critical mass. His opponents seized the opportunity to label him a “flip-flopper”, implying that he didn’t stand up for his beliefs.

I think they’re both symptoms of the same thing: the Internet. We all get excited that Obama, MoveOn.org, and other groups use social media and big data to mobilize and react to voters, volunteers, and donors. At the same time, legislators cry foul over gotcha journalism, ballot-box budgeting, and paper-thin politicians who change their positions at the slightest breeze of likes and retweets.

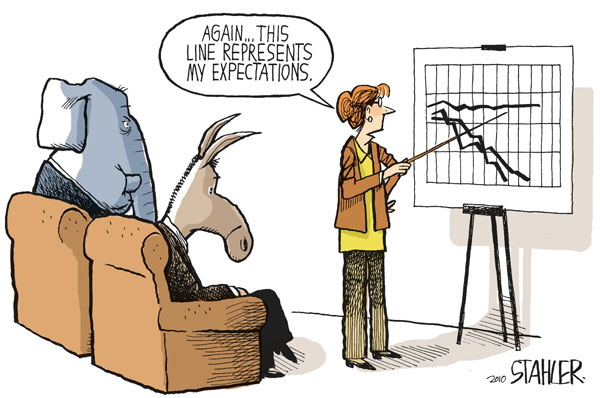

The criticisms resonate with me. We already worry that our politicians are gridlocked, inauthentic, and don’t follow through on their promises. A/B testing and instant online feedback will make this even worse, right?

I wonder. The whole point of representative democracy is for our elected officials to represent us, to make laws and interact with other officials in the ways we want. Historically, we’ve had only had a handful of tools for this: the heavy sledgehammer of elections, the press grenade we can’t hope to aim, opinion polls about as accurate as rusted-out nails, and finally the tiny glasses screwdrivers: letters, phone calls, and town hall meetings with actual constituents. These tools may get the job done, but they’re not great.

Technology can clearly help. Online petitions and micro-elections, direct communication over social media, and instantaneous, 24/7 press cycles now give politicians a continuous stream of feedback. Groups like Code for America, Data.gov, and GovHack praise this new world of empowered citizens. They’re usually silent on the drawbacks, though, such as flip-flopping.

Take Obama’s gay marriage reversal. I don’t know if modern politicians change their minds more often due to technology, but if they do, would that be so bad? Say you supported gay marriage before Obama did. Aren’t you glad he come around eventually, instead of holding firm due to outdated public opinion polls – or worse, to avoid being accused of waffling?

Here’s a question: what if Obama didn’t actually change his mind at all? What if he changed his public position, but still personally opposed gay marriage? Would it matter whether he supported it in private or not, as long as he consistently supported it in public and voted for it?

The knee jerk reaction is, of course it would matter! But I don’t know. If his public actions were indistinguishable, then arguably it wouldn’t matter at all. Of course, that’s pretty unlikely. In reality, your personal beliefs motivate you to work hard and fight for what you believe in. Caring begets results.

Realistically though, most politicians care about getting re-elected more than any single issue. Modern technology lets them take our pulse faster, cheaper, and better than ever before. If that helps them hew more closely toward our desires so they can win elections, so much the better.

As usual, the conclusion isn’t that technology is inherently good or bad for politics, but that it amplifies and accelerates what we already want. In this case, though, I think that is inherently good. Representative democracy is all about getting us the government we want. If technology helps, so much the better! It may not solve the money part, or the gridlock or media echo chamber or any number of other problems, but I’ll take what I can get.

(Of course, that begs the question: is the government we want actually the government that’s best for us? I’m not convinced. But that’s a post for another day…)

Technology is a tool that can be used for good or evil!

@schnarfed none of the above?

Yes, this!

Related: one thing I think people are starting to realize is that technology makes doing good easier, but it also makes doing bad easier. Yes, because of technology, it’s now easier to con people on a massive scale. But that comes along with the people to educate and enlighten people on that same scale. Technology is ultimately neutral, and any imbalance in the amplification of good or evil is ultimately a reflection of how we as human beings behave.

In the case of democracy, the assumption we make is that democracy is ultimately good for us (which can be a heavy pill to swallow, looking at some of the way groups vote on certain topics). Technology makes it easier for our heads of state to speak for the whole body, even if the individuals in those roles don’t agree.

…or for its intended purpose, slapstick humor.

also, Patrick, maybe you’d like to subscribe to my newsletter. :P https://ryandc36.wpcomstaging.com/2012-08-13_technology_makes_us_more_who_we_are

I guess it all depends on which of the two following statements is true:

A) Are you electing the person, putting faith in that individual to uphold the things you believe in because they believe in them? If so then waffling is an issue, even if tools are used to do it, because the fundamental reason why the individual representative is in office is because of who they are.

B) Are you electing merely a viewpoint, the person being a proxy to this viewpoint? If so then (setting aside the absurdity of having a proxy to say for you what you can say perfectly well yourself at a voting booth, and setting aside the game ‘broken telephone’ as an example of how even a basic sentence once passed between multiple parties becomes something else) analytics are probably the most powerful tool any politician can have. A pledge to follow analytics to the letter should guarantee that politician perpetual terms in office, as they will always have the majority.

“The whole point of representative democracy is for our elected officials to represent us, to make laws and interact with other officials in the ways we want.”

I’m not sure if that’s really the best way to look at it. Many political issues are very difficult for most people to fully understand, and so people tend to have very odd political opinions that are themselves influenced by social opinion trends. Maybe a better way to think about democratic elections is that they are not to choose people who will simply do what we want them to… if that were the case, it would be a lot more efficient, and accurate, to hire a technocrat who does full scale opinion research and crafts policy around those data.

No, a better way to think about elections in a democracy is that we are hiring professional politicians that broadly conform to a set of political values but have the technical knowledge to translate those values in to policy and the political acumen to make those policy a reality.

Hate simplistic metaphors, but if you hire a building contractor, do you really want someone who is going to do exactly what you say, even if you want something that you don’t realize will make your building fall down? No, you want someone who generally understands the style of design you like and has the technical knowledge to build things that you cannot.

Nice post, Ryan! Agreed, technology is neither good nor bad in this case – it has become a tool for politicians to better gauge public opinion and adjust accordingly… along with their approval rating :)

D. Both A and B. This one has so many facets and grey areas.

What Patrick and Kasey said. But there is more than the “tool” argument, such that ONLY (A) or (B) cannot be chosen:

You don’t specify the frame of reference.

“(A) Tech is good for government” … is that “Tech brings a good government to the people” measured on transparency, capability, efficiency, etc. Or is that “Tech is good for the institution of government to feed itself and stay in power”, through (say) an Orwellian monopoly on and use of tech capability.

That frame of reference applies to (B) also.

(C) is pretty much one frame of reference, but give me more time and sleep, and we’ll see if I can figure out how it can be twisted :-P

yup. btw, you’re both replying to the question, not the article, right? i meant it just as a cutesy hook to get people to click through, but i probably should have been more straightforward. :P

Correct :-) … generally, I agree with the basic conclusion of the article: by adhering more closely to our desires [in order to be re-elected] we get better representation.

But at a practical level, the 2-party system pretty much kills that theoretical feedback loop, since the parties need to polarize the discussion. Thus, you end up with a party representative that matches you on 6 or 7 (of 10) points, rather than selecting a representative that more closely aligns to reach a 9 or 10.

DecodeDC‘s latest episode, Future Congress, talks a lot about this. Andrea Seabrook makes the important point that Congress members in particular need to geotarget very precisely to just their congressional district, which makes it hard to use social media and many other online services because they don’t support that well. Much of this still applies for politicians at the state and federal level, as well as general consumer sentiment and approval rating, but it’s still worth noting.